Unfortunately this blog is no longer checked on a regular basis. Please do continue to post your comments though, these will still be approved.

-

Join 277 other subscribers

Children’s Lives

Tweets by childrens_lives-

Recent Posts

- Update

- At School No.16: Children’s Parents

- At School No.15: Teacher’s Lives

- At School No.14: Disease and Cleanliness

- At School No.13: Charity

- Displaced Childhoods: Oral History Society annual conference

- At School No.12: Child Poverty

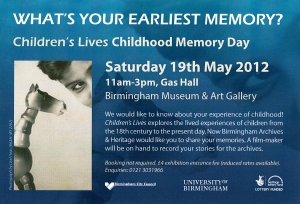

- What’s Your Earliest Memory?

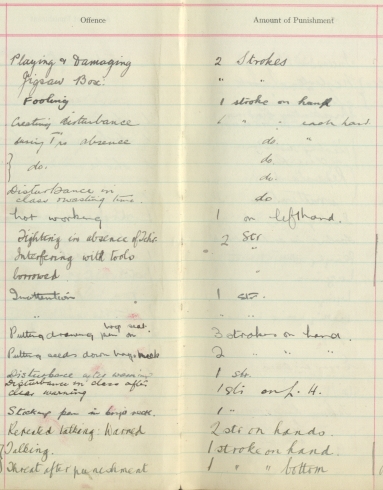

- At School No.11: Corporal Punishment

- At School No.10: Corporal Punishment

- At School No.9: Violence and Injuries

- At School No.8: Violence and Injuries

- At School No.7: The World at War

- At School No.6: The World at War

- At School No.5: Truancy and Criminality

childrens lives

- August 2014 (1)

- June 2012 (2)

- May 2012 (6)

- April 2012 (5)

- March 2012 (5)

- February 2012 (4)

- January 2012 (4)

- December 2011 (3)

- November 2011 (6)

- October 2011 (4)

- September 2011 (2)

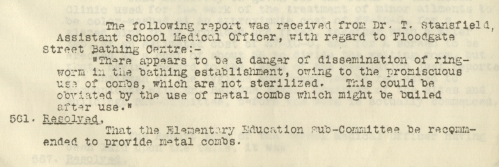

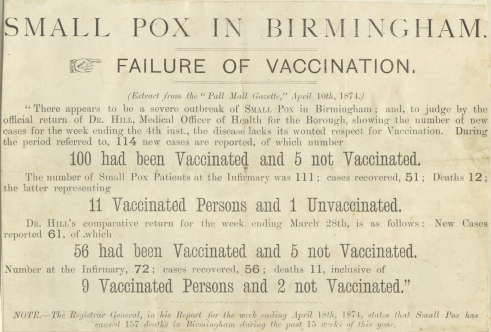

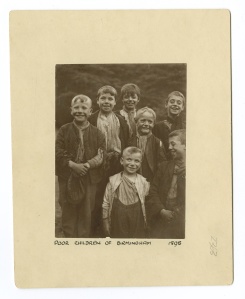

- apprentices archives benjamin stone birmingham birmingham museum and art gallery braille cadbury charity childhood child labour children children's homes chimney sweeps christmas cinderella cotton mills crime cruelty davos deaf culture disease drawing education emigration emma barton evacuation floodgate street floodgate street board school four dwellings high school health heritage homelessness hospital illness indentures injuries ivy harper julia lloyd kunzle lip reading lisel haas maria cadbury middlemore moon type nick hedges norton school nspcc nursery nursery rhymes pantomime parents pentland photography poverty punishment reformatory school selly oak nursery school SHELTER sign language street robins switzerland teachers theatre royal tinkers farm road school travel truancy tuberculosis vaccination war waverley school world war world war two young people young people's archive

Children\’s Lives

childrens lives